The Triangle Table

As part of the reorganization of the office space for the Mathematica

user interface team at Wolfram Research,

Inc.

, we needed some conference tables. Office supply catalogs are really

quite depressing, and the fancy stuff is so insultingly overpriced I'd never

consider it. There was just no choice: I had to make some tables for us.

The results were this Triangle Table and the

Periodic Table

.

The Triangle Table was designed to fit two sofas along two of its edges,

while not taking up too much of the rest of the floor space. By cutting

off half of an ordinary rectangular table, I preserved the full amount of

sofa frontage, while cutting the square footage in half.

To ensure a pleasing degree of asymmetry it made sense to have two different-length

sofas, and of course if you're making a right triangle where the two edges

by the right angle are not the same length, it should really be a 3-4-5 triangle.

The first thing anyone thinks of in connection with triangles is naturally

geometry, specifically constructions with ruler and compass of various sorts

of bisectors, inscribed circles, and so on. So I thought it would be

fun to inlay the table with contrasting woods so as to illustrate some particularly

attractive construction.

Eric Weisstein's MathWorld

website provides a wealth of possible

triangle constructions

. Unfortunately it was offline at the time because of a lawsuit against

it filed by his publisher, CRC Press LLC. Fortunately, he works for

my company and we were the ones defending him against the lawsuit, so I had

access to the material in MathWorld privately. Otherwise, I don't think

the table would have been made this way.

I searched MathWorld looking for a construction that was pretty, had enough

lines but not too many, and looked good in a 3-4-5 triangle. I settled on

the Spieker Center

. If you make your own Triangle Table, pick a different one, because

there are lots of good ones in there.

Here, in words and pictures, is how the table was constructed. Click

on any picture to see a large version open in a separate window.

The starting point of any table is a tree: I don't have a picture of the

tree most of the wood for this table came from, but I do have a picture of

the very next step, the rough sawn 2x8 walnut lumber I started with:

I got a huge amount, much more than in this picture, at an auction for next

to nothing, which is why I build just about everything

out of 2x8 walnut.

Starting from rough sawn lumber, the first step is planing it to a consistent

thickness (just under two inches in this case):

Then you joint one side:

Then run it through the table saw to get the other side parallel:

Then you joint the sawn side to make it smooth, giving you S4S stock to

work with:

After carefully selecting the boards I wanted to use (this stuff is quite

knotty, so that took some time), I biscuit joined them edge-to-edge into three

slabs large enough to cut three sub-triangle from. These three sub-triangles

were assembled into the whole table one at a time. (Note the large sheet

of paper it's on: It's hard to see in the pictures, but my first task in

making the table was to use actual ruler and compass to lay out a full-size

plan. Sometimes the old ways are the best ways... This is in

fact a 60-80-100 inch triangle.)

The joints between the sub-triangles are at the midpoint of each angle (that

is, they are the angle bisectors). This means there should be no stress

on the joint as the wood expands and contracts, because the grain is meeting

at the same angle from both directions.

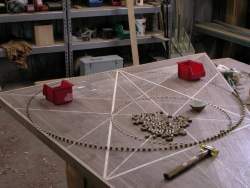

Then came the bondage phase of construction:

The inlay lines were made of oak and maple wood. The oak was from

the same auction as the walnut, while the maple was from Chris Carlson's

front yard. Here's Chuck and his sawmill cutting it up a few years

earlier:

I cut, planed, re-cut, and re-planed the inlay lines into strips about 5/16"

thick and 1/4" or 3/8" wide respectively:

Then I just had to use a router to cut slots, and pound the strips into

the slots.

Here's a closeup of one of the intersections (yes, they are supposed to

miss like that...):

One important point to note is that there is an inlay line right on top

of each of the three joints where the three sub-triangles meet. This

significantly reduces the need for those three pieces to meet perfectly,

which is a good thing considering how big they are and how much a tiny error

in angle would be visible if it weren't covered by an inlay line. I

am a great believer in not doing things that look bad if they aren't perfect.

I worried about how to do the circles. Cutting or bending strips to

make a circular inlay is a pain to say the least. So I decided that

people often use dotted lines in this sort of diagram, so I could too. I

drilled holes and made plugs out of scraps of wood using some plug cutters:

Here are some closeups of the circles meeting the lines:

Note that the second example demonstrates how tight the intersections are,

if I may say so myself. The dots are supposed to be equidistant from

the center of the intersection, and they are supposed to intersect the one

line by an equal amount on each size. The lines are 1/4" wide. I

think it's pretty close.

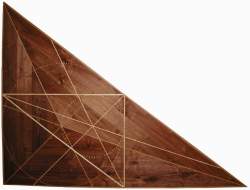

After the surface was all sanded down smooth, here's the final tabletop

before varnishing:

For the legs I wanted something that would not get in the way of feet, and

would provide some storage space for a conference phone, etc. I built

a shelf supported by three legs (of course everything, including the legs,

are 3-4-5 triangles:

Then it was off to the Amish for a coat of their best high-tech catalytic

urethane varnish, and it's done:

In the 6 months that it's been installed, a couple of very small cracks

have appeared, probably due to further drying of the walnut. The humidity

control in my shop it not what it should be. Fortunately, I have a

good 5/16" thickness in the inlays, and after it's totally settled in and

done with any shifting it's going to do, maybe in 3-5 years, I'll take a

look at the cracks and if they seem annoying I'll just sand the whole thing

down to bare wood, fill the cracks with wood putty and have the Amish re-varnish

it. That should hold it for a couple of centuries at least. Unless,

of course, the inlays never allow it to stabilize, in which case it will

just always have a few hairline cracks in one place or another. No

big deal.

One fact sure to amuse future generations is that on the bottom side of the

table is a complete replica (minus the circles) of the same construction

as the top, only sloppier. I did one on the bottom for practice first,

and I also figured that by having identical inlays on the top and bottom,

any stress introduced would be balanced and would never cause the whole thing

to warp. It also hides the joints between the three sub-triangles from

both directions, so no one can ever tell how close I got those joints.

If you've read this far, be sure to check out my

Periodic Table

. It's less complex from a wood working point of view, but more more

elaborate in other ways, and its website is definitely way more complicated

than this one. You can also see a list of all the

woodworking projects

I have online.